This Family Found an Old Suitcase and It Led Them to a Fortune Stolen by Nazis

In 2009, Antony Easton was sorting through his late father’s belongings in a small apartment in Lymington when he found an old brown suitcase. It contained German banknotes, personal documents, and a birth certificate that didn’t match his father’s name. His father, Peter Easton, had been born Peter Hans Rudolf Eisner, a member of one of pre-war Berlin’s wealthiest Jewish families.

That suitcase opened a path to a hidden history of stolen art, lost property, and lives erased by Nazi persecution.

A Family Name That Disappeared in Silence

Peter Easton spent most of his life in England and never talked openly about his childhood. He presented himself as English and distanced himself from his German background. He raised his son, Antony, without sharing that he had once been Peter Eisner, born in 1924 in Charlottenburg, Berlin.

After Peter’s passing, Antony discovered a carefully organized suitcase that carried his father’s life story. Through the items he found, the son learned that the family had fled Berlin in the late 1930s. The leather case was full of information that connected their past to events they had never spoken about. It told the story of a Jewish family that had once lived in immense wealth, only to lose everything to a regime that targeted them because of their identity.

A Steel Empire Lost to Forced Sales

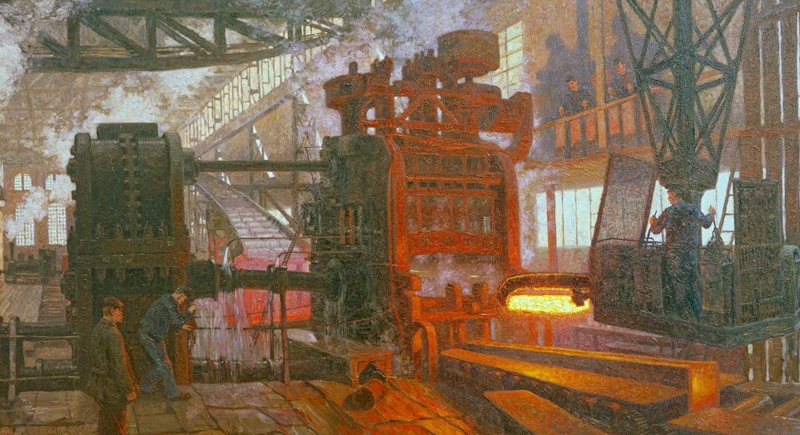

Image via Wikimedia Commons/akg-images.de

The Eisner family once co-owned a significant steel business in Germany. Heinrich Eisner, Antony’s great-grandfather, co-owned Hahn’sche Werke, a company that produced tubular steel for railways and weapons. Their holdings stretched across Germany, Poland, and Russia. The family lived in Berlin in a six-storey home with marble floors, employed servants, and traveled with chauffeurs.

When Heinrich died in 1918, his son Rudolf took over. The business survived World War I and the economic instability that followed. But in 1938, the company was forced into a sale under pressure from the Nazi regime. It was acquired by Mannesmann, a Nazi-aligned conglomerate, at a drastically reduced value.

Unfortunately, these were not voluntary transactions. In fact, historical records and expert reviews classify them as “forced sales,” common in the systematic seizure of Jewish-owned assets. The takeover of Hahn’sche Werke removed the family’s core source of income and reduced their influence. In today’s value, the Eisner losses would be measured in billions.

The Betrayal Behind a Promised Deal

As Nazi persecution intensified, the Eisners began looking for ways to protect what remained. One name that kept appearing in the records was Martin Hartig. He had spent time at the Eisner estate in the 1930s and was recorded in the guestbook as a friend of the family. He was a tax adviser and not Jewish, which gave him certain protections. Rudolf Eisner signed over control of the family’s properties to Hartig under the belief that this move would shield the assets.

Hartig kept the properties but never returned them. Documents in German archives show that Hartig transferred them into his own name shortly after gaining power of attorney. These were not hidden transfers, but processed through legal channels and approved under laws specifically designed to strip Jews of property. Later generations of the Hartig family still live in one of the seized homes. Though some relatives believed Hartig helped the Eisners, the documented evidence shows a different outcome.