The Robin Hood of the Great Depression Who Freed Farmers From Debt

The Great Depression did not just wipe out savings. It pushed thousands of farm families toward foreclosure, often through paperwork they barely understood and courts that moved faster than their lives could recover. In those years, resentment toward banks and sheriffs ran deep across rural America.

Out of that anger, an unlikely figure took on a mythic role. Charles Arthur Floyd, better known as Pretty Boy Floyd, was a violent bank robber by record, but to some struggling farmers, he came to represent resistance to a system they felt had already turned against them.

When Paperwork Became the Enemy

Image via Canva/rick734’s Images

The early 1930s were punishing for rural families, especially across Oklahoma and much of the Midwest. Banks tightened credit, auction notices arrived abruptly, and sheriffs carried out foreclosures with limited discretion. For families tied to the same land for generations, debt records marked the loss of livelihood, continuity, and control.

Within that atmosphere, stories took hold that Floyd destroyed mortgage papers and loan records during bank robberies. The details were inconsistent, and proof never surfaced, but the story spread anyway. In places where banks and courts felt distant and unyielding, the notion of paperwork being torn apart resonated on its own terms.

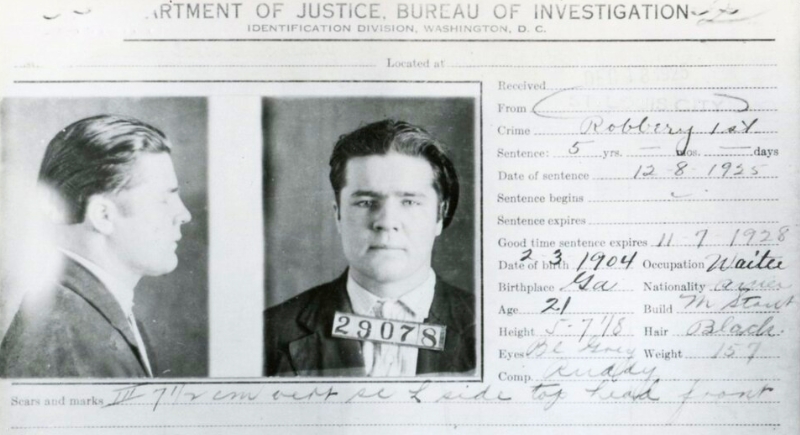

The Making of a Folk Hero

Image via Wikimedia Commons/1928 LAw enforecment 1934 Law enforcement 1934 FBI

During the early years of the Depression, Floyd moved constantly across the Midwest, robbing banks and staying ahead of the law longer than most criminals of his time. He relied on speed, heavy firepower, and frequent relocation, which made him difficult to track and added to his reputation.

To police, he was reckless and dangerous. In parts of eastern Oklahoma, though, people called him the Robin Hood of the Cookson Hills. That label had less to do with generosity and more to do with timing.

When foreclosures were emptying farms and banks felt untouchable, attacking financial institutions carried symbolic weight. Floyd did not have to hand out cash to be seen as defiant. Hitting banks during a period of widespread loss was enough.

Some locals hid him or refused to help authorities. It was not because they approved of violence, but because resentment toward banks and officials ran deeper than fear of an outlaw.

Myth Versus Proof

There is no surviving evidence that Floyd regularly destroyed mortgage records or erased debts. Historians still debate whether those acts happened at all, but the lack of proof did little to weaken the story.

The rumor spread because it felt believable. Banks controlled contracts and deadlines. Farmers worked around weather, seasons, and shrinking margins, while courts ran on schedules that ignored agricultural life.

Even without legal impact, robbing banks looked like an attack on the source of that pressure.

The legend never canceled the damage. Floyd was linked to multiple killings, and his robberies were chaotic and dangerous. Banks increased security, and robberies became riskier for everyone involved. To law enforcement, he remained volatile and violent.

By 1934, after the death of John Dillinger, federal authorities named Floyd Public Enemy Number One, placed a large bounty on him, and intensified the hunt.

A Death That Cemented the Legend

Image via Getty Images/LPETTET

Floyd was killed in October 1934 in an Ohio cornfield after a confrontation with federal agents. Almost immediately, accounts diverged. Some witnesses said he resisted. Others claimed he was wounded and later shot. The absence of a single, definitive version became part of the story itself.

His funeral drew tens of thousands of people, making it one of the largest in Oklahoma history. The turnout reflected widespread frustration and grief. Many attendees were responding to what Floyd had come to represent, not the violence he committed.

Floyd’s reputation persists because it illustrates how moral judgment shifts during collapse. In stable periods, crime is easy to condemn. When systems break down, perspectives change. The same individual can be viewed as a murderer by some and a symbol of resistance by others, depending on whose interests institutions serve.

The mortgage-burning legend survives for similar reasons. It captures a moment when paperwork felt more punishing than force, and when destroying records seemed, emotionally, like justice. Floyd became attached to that belief, regardless of his actual conduct.

A Cautionary Legacy

Calling Floyd the Robin Hood of the Great Depression does not excuse his actions. It explains the conditions that shaped his image—conditions of economic despair and legal systems that did not feel protective.

Floyd did not reverse the Great Depression or rescue American agriculture. But the myth that has built up around him reveals what can happen when institutions fail on a broad scale. In moments like that, even a bank robber can be remembered as someone who challenged the system, at least in story.