The Dunning-Kruger Effect: Why Incompetent People Think They Are Experts

In 1995, a man robbed two banks in Pittsburgh with his face fully visible on surveillance cameras. He later claimed he had smeared lemon juice on his skin, believing it would make him invisible to the cameras, the same way it works with invisible ink. His strange confidence caught the attention of psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger, who went on to explore how people with the least knowledge often carry the most self-assurance. Their work gave this phenomenon its name: the Dunning-Kruger effect.

The Science Of It

Image via Wikimedia Commons/Sciencia58

The first experiments, published in 1999, tested students on humor, grammar, and logic. After completing the tests, participants estimated their own performance. The least skilled students consistently rated themselves above average, while those who actually excelled often underestimated their results.

Researchers described this as a “double burden.” People lacking skills not only performed poorly but also failed to recognize their mistakes. The very knowledge needed to judge their own performance was missing. This explains why someone who loses repeatedly in a debate may still think they argued well—they lack the expertise to recognize how weak their case really was.

How It Shows Up In Everyday Life

This effect extends well beyond classrooms and labs. It can appear at family dinners, when a relative speaks with confidence about science despite not having studied it in years. Studies show similar patterns across many fields: weak drivers, inexperienced chess players, and people with limited financial knowledge frequently rate themselves above average.

On the other end of the spectrum, true experts sometimes underestimate themselves. They may assume their knowledge is more common than it is, which leads to modesty in areas where they actually outperform most people. The result is a strange mix where both the least skilled and the most skilled misjudge their own abilities.

Offices and boardrooms provide plenty of real-world examples. Research has shown that self-confident employees often get promotions and raises faster than more qualified but less vocal colleagues. Managers frequently confuse confidence with competence, and the effect snowballs.

This mismatch causes headaches for teams. An overconfident manager may reject sound ideas, resist feedback, and push the wrong strategies. Meanwhile, skilled employees may struggle to gain recognition because they are less forceful in presenting their expertise. Over time, these dynamics strain collaboration and weaken performance.

Why We All Fall For It

Image via iStockphoto/FluxFactory

Nobody escapes this effect completely. Everyone has areas of ignorance they underestimate. A scientist might excel in research but lack writing skills. A talented writer may overrate their grasp of finance. Because we can’t recognize what we don’t know, blind spots sneak in across different parts of life.

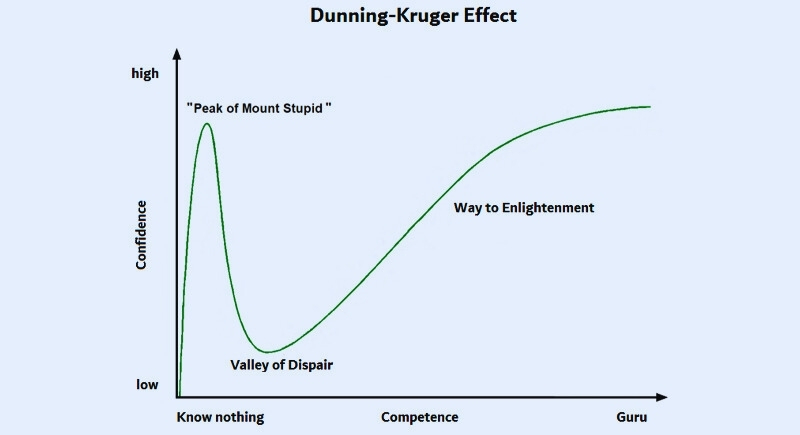

Another reason is the misleading confidence that comes with learning a little. People often gain early knowledge on a subject and then overestimate their understanding. As they dig deeper, confidence dips because they begin to see the full complexity. With enough expertise, confidence rebounds, but by then, they usually appreciate how rare true mastery is.

Avoiding this trap starts with staying open to correction. Asking for honest feedback, even when it stings, offers a better measure of ability. Expanding knowledge through study and practice is another safeguard, because growth exposes the gaps we didn’t see before. Experts also benefit from remembering that strength in one area doesn’t automatically apply to another.

The Dunning-Kruger effect shows that confidence and skill do not always match. Sometimes the least qualified person dominates the conversation, and sometimes the most capable holds back. The challenge is knowing where you stand and being willing to check before declaring yourself the expert.