13 Ways to Talk to Your Kids About Suicide

Talking about any death with your child can be hard. Suicide is even harder. And it is becoming increasingly unavoidable.

The national suicide rate is up an astonishing 25 percent, compared to 20 years ago.

Each of the tens of thousands of people who die of suicide each year leave an average of six loved ones behind — many of them children and young people — to make sense of what is, to most, a senseless act.

What’s most tragic, though, is that suicide is preventable. That’s why it so important to talk about it with the people you love most — your children.

Say the Word

It’s okay to say the word suicide — necessary, even, when the topic is already out there.

While “suicide contagion” is a thing — especially among teens — the word itself is not dangerous.

“You can’t prompt suicide by talking about it or asking about it,” said Thea Gallagher, clinic director at the Center for Treatment and Study of Anxiety at the University of Pennsylvania, in a story for Today.

In fact, saying the word could be life-saving. Often the most important thing a person can do is to ask someone who appears to be in crisis, “Are you thinking about suicide?”

Ask Them What They Know

All too often, adults will launch into a (thoughtful, prepared) monologue about a difficult topic — not knowing where their child really is, emotionally or psychologically, or how much information they already have.

Some children know a lot more about difficult topics than they let on. Other children, however, can be almost oblivious, or deeply misinformed.

The best way to counter misinformation and not overshare is to ask questions first.

You can say, “What have you heard about X?” to get a baseline for what they do and don’t know about the person who died by suicide.

Then follow up with something straightforward, such as, “Yes, X died, and I am very sad about it,” to prompt a fuller, more emotional response.

Be Age-Appropriate

A 3-year-old and a 13-year-old require honest conversation about suicide, yes, but to different degrees. Dr. Deborah Gilboa, a parenting expert, helped frame some helpful age-by-age guidelines for Today.

– Preschool: Young children don’t necessarily understand the permanency of death. They are pretty clear, however, about emotions. If a child is asking about a death by suicide, a commonly suggested tactic is to talk about simple emotions — like deep sadness — and, says Gilboa, to frame suicide like a disease, such as cancer.

– Elementary school: Similarly, school age children benefit from simple language and framing suicide as a disease. By age 8, most children understand what death is and what it means to kill oneself. But they don’t necessarily understand, say, severe depression. Gliboa suggest letting children guide the conversation.

– Middle school: By middle school, kids may already have firsthand experience of depression or other mental health issue associated with suicidal thoughts, says Gilboa. Parents might begin to ask if a child has ever thought about suicide or if any of their friends have.

– High school and beyond: It’s time to talk directly to your child about suicide. “We are not going to say ‘if.’ Not ‘What would you do if you were worried about this.’ But, ‘What will you do when you are worried about yourself or your friends?’” said Gilboa. “It is nearly impossible for a child to get through high school without knowing someone with a mental health condition.”

For all ages, it’s important for a child to know that they are safe talking with you about such a tough topic. Listen. Be non-judgmental. It is not the time to debate whether suicide is right or wrong.

Tell the Truth

Lying about a death by suicide simply adds to the shame and secrecy that already surround the topic. And it perpetuates the culture in which suicide thrives.

That’s why, for instance, Eleni Pinnow, a professor at the University of Wisconsin-Superior, wrote about her sister’s suicide in her sister’s obituary — and elsewhere.

“The lies of depression can exist only in isolation. Brought out into the open, lies are revealed for what they are,” she wrote in The Washington Post. “Here is the truth: You have value. You have worth. You are loved. Trust the voices of those who love you. Trust the enormous chorus of voices that say only one thing: You matter.”

Dispel the Myths

Like with any taboo subject, myths about suicide abound. They must be recognized and spoken about to dispel.

– Myth: A suicidal person just wants to die.

– Truth: They want the pain to stop.

– Myth: A suicidal person is too weak.

– Truth: They don’t have the tools to deal with this particular crisis.

– Myth: A suicidal person is just looking for attention.

– Truth: They are in need of help.

Stop the Blame Game

According to certain sources, designer Kate Spade wrote to her daughter before taking her life, “This has nothing to do with you… Don’t feel guilty.”

But it’s inevitable for suicide survivors to look for blame.

Suicide leaves so many unanswered questions, the first and foremost of which is, “Why?” But suicide happens for myriad, complicated reasons — not one thing that one person said or did.

Even in egregious examples of what’s called “bullycide,”where a bullied child kills themselves, the bullying alone is likely not the sole factor.

Talk About Mental Illness

“There is no single cause to suicide,” The American Foundation for Suicide Prevention writes. “It most often occurs when stressors exceed current coping abilities of someone suffering from a mental health condition.”

Mental health conditions are often precursors to suicide — most commonly being bipolar disorder, depression, psychotic disorders like schizophrenia and post-traumatic stress disorder. And mental health conditions affect far more people that most of us realize — roughly one in five.

That said, mental health is just a piece of the puzzle. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that 54 percent of the people who have died by suicide did not have a known mental health condition.

While it’s true that many people do go undiagnosed, the statistic also underscores just how complicated, complex and varied the reasons for suicide can be. Often, we just don’t know why.

Translate the Media for Them

Or better yet, when suicide coverage is in full swing, turn it off.

In the onslaught of stories, headlines, tweets and updates after someone famous dies by suicide, there’s an obsession with how they committed suicide, why they did it, who (or what) is to blame — and all the things that anyone who has ever met the person think and feel.

Taken as a whole, the coverage can easily slip into the sensationalistic.

It’s not limited to news, either. Take the Netflix series about teen suicide, “13 Reasons Why.”

“When teens consider suicide, they often fantasize about the aftermath,” psychotherapist Amy Morin wrote in a critique of the show for Psychology Today. Morin says the show does harm in the way that it romanticizes suicide, makes it look like a reasonable solution and presents suicide as a way to “teach people a lesson.”

Use the Right Language

The language around suicide is changing, and for important reasons. Professionals no longer say “commit suicide” — as suicide shouldn’t be akin to a sin or a crime.

“We suggest more objective phrasing, like ‘died by/from suicide,’ ‘ended their life’ or ‘took their life,'” suicide awareness activist Dese’Rae Stage told CNN.

“If we’re using the right language, if we’re pulling negative connotations from the language, talking about suicide may be easier,” she said.

Pain Isn’t Always Visible

“Everyone you meet is fighting a battle you know nothing about. Be kind. Always.” The quote has been attributed to everyone from Plato to New York Times best-selling author Brad Meltzer, but it’s true regardless of who said it first.

Severe depression, anxiety, and other mental health disorders can be right there in front of you, behind dazzling smiles, outward signs of success or envy-worthy social media posts. It can be deeply unnerving when someone “so full of life,” and with no outward signs of internal crisis, can still be in enough pain to take their own life.

But it’s also a lesson about tempering what we believe about the lives of other people — even those we know well — and to have empathy.

Talk About Warning Signs

We can’t accurately predict suicide, but there are almost always signs. Key warning signs, from National Alliance on Mental Illness, include:

- – Threats or comments about killing themselves, also known as suicidal ideation, can begin with seemingly harmless thoughts like “I wish I wasn’t here” but can become more overt and dangerous

- – Increased alcohol and drug use

- – Aggressive behavior

- – Social withdrawal from friends, family and the community

- – Dramatic mood swings

- – Talking, writing or thinking about death

- – Impulsive or reckless behavior

There are also risk factors. Severe depression and suicidal thoughts can also be triggered by stressful life events, like divorce or job loss, exposure to other suicides, harassment or bullying, as well as a family history of suicide.

Teach Them how to Help Others

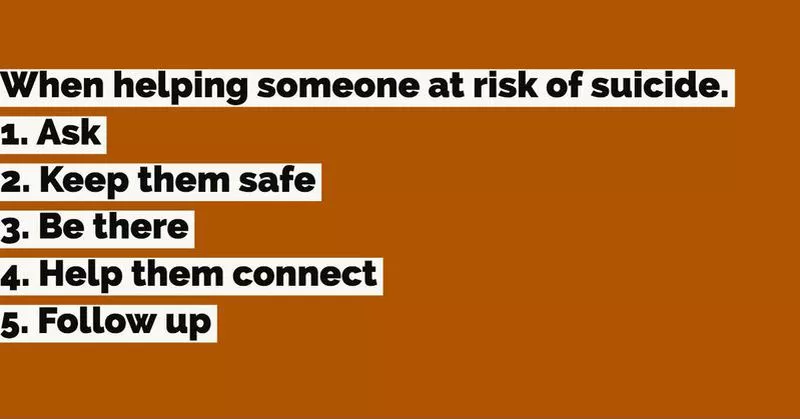

The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline has a straightforward, five step plan for helping someone who might be at risk of suicide.

- – Ask: Ask the person directly if they are considering suicide.

- – Keep them safe: Remove potentially dangerous items, such as weapons or drugs.

- – Be there: Stay with that person.

- – Help them connect: Make it easy for that person to find help.

- – Follow up: Don’t just intervene once, stay connected.

Learn more at www.bethe1to.com

Show Them how to Ask for Help, Themselves

“Sometimes the bravest thing you can do is ask for help.” It’s a well-worn inspirational quote, but one that has even more resonance when it comes to suicide.

When children see the adults in their lives struggling and hear them talk through their problems and seek help from family, friends, counselors or therapists, it models a certain kind of perseverance and resilience.

Challenges exist — and they can be overcome. Whatever darkness or difficulty exists right now, it too shall pass. The underlying message: Life is hard, but it is worth living.

If you or someone you know are experiencing suicidal thoughts, call 911, or call the National Suicide Prevention Hotline at 1-800-273-8255 or text HOME to the Crisis Text Line at 741741.