17 Reasons People Died Young 100 Years Ago

A century ago, making it to your 50th birthday meant you’d beaten the odds. The average life expectancy in the early 1900s hovered around 50 for men and just a few years more for women. That wasn’t because people simply aged faster—it was because diseases, poor sanitation, and limited medical knowledge made surviving childhood and early adulthood a real challenge. Here’s a closer look at some of the major threats that cut lives short back then—illnesses many today have never had to worry about thanks to modern medicine.

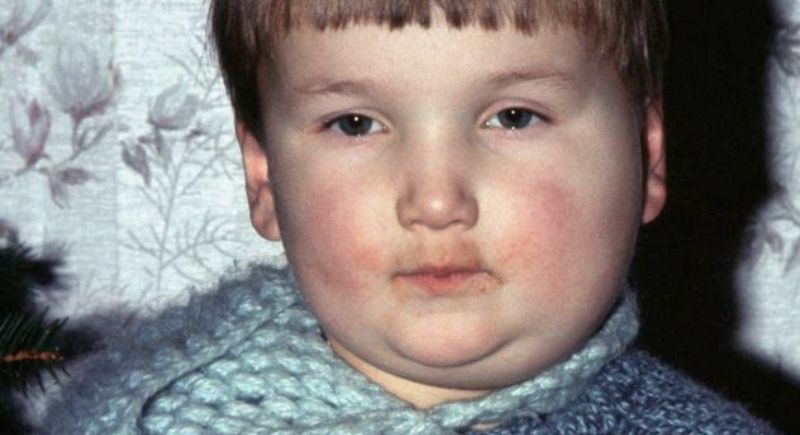

Diphtheria

Credit: flickr

Diphtheria was one of the most feared childhood diseases of its time. It attacked the respiratory system by forming a thick, grayish membrane across the throat that could close off airways entirely. Children often struggled to breathe as their windpipes narrowed, and death by suffocation or heart failure was common. The bacteria that caused it spread easily through coughs and sneezes. An outbreak could sweep through entire towns and left families with no options beyond isolation and prayer.

Haemophilus Influenzae Type B (Hib)

Credit: Getty Images

This bacterial infection hit young children particularly hard. Hib could cause meningitis, which led to brain swelling, high fevers, seizures, and in many cases, permanent hearing loss or developmental delays. Physicians had little more than observation and basic support to offer. It wasn’t uncommon for a child to fall seriously ill within hours, and the outcomes varied widely—some recovered, others faced lasting disabilities, and too many didn’t survive at all.

Hepatitis A

Credit: Getty Images

Hepatitis A thrived in places where sanitation lagged behind population growth. It was usually contracted through contaminated food or water, often in areas without reliable plumbing or proper waste management. The virus inflamed the liver and with symptoms like jaundice, vomiting, and prolonged fatigue. While most people eventually recovered, the illness could take weeks to pass and sometimes triggered more serious complications. In poorer communities, entire households would fall sick at once, which stretched families and healthcare systems thin.

Hepatitis B

Credit: Getty Images

Unlike its cousin Hepatitis A, Hepatitis B didn’t always show itself right away. People could carry it for years without symptoms, while the virus quietly damaged the liver. It was spread through blood and bodily fluids—during childbirth, unsterilized medical procedures, and sometimes even in workplaces like barber shops or dental offices that lacked strict hygiene standards. Over time, it could lead to cirrhosis or liver cancer.

Measles

Credit: Getty Images

Measles was practically a rite of passage for children—but that didn’t mean it was harmless. The virus caused high fevers, a widespread rash, and severe coughing. Complications like pneumonia or encephalitis were not uncommon, especially in undernourished or younger children. Nearly every child contracted measles before adulthood, and while many survived, a significant number either died or were left with long-term impairments.

Mumps

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Before the vaccine era, mumps spread easily among children and teenagers. It caused painful swelling of the salivary glands, often making it difficult to eat or talk. In some cases, especially in adolescent boys, it also affected the reproductive organs and could lead to infertility. Adults who caught mumps typically experienced more severe symptoms. Entire classrooms or workforces could be knocked out for days, and in rare cases, the virus triggered meningitis or hearing loss.

Pertussis (Whooping Cough)

Credit: Canva

Pertussis was especially dangerous for infants. The disease caused violent coughing fits that made it hard to breathe. Babies were often seen gasping between coughs and turning pale or blue from lack of oxygen. At the time, doctors had no antibiotics or effective treatments. Parents tried everything they could—steam baths, herbal remedies, even prayer—but survival often came down to the child’s strength.

Pneumococcal Disease

Credit: Getty Images

Pneumococcal bacteria were responsible for a wide range of serious illnesses, including pneumonia, meningitis, and bloodstream infections. Pneumonia, in particular, was a leading cause of death, especially in the very young and the very old. Symptoms came on quickly—fever, chills, chest pain, and difficulty breathing. Without antibiotics, there was little doctors could do beyond bedrest and fluids. The disease often spread in crowded living quarters or among soldiers during wartime, where close contact made infection almost unavoidable.

Polio

Credit: flickr

Polio completely reshaped lives. The virus could cause anything from mild flu-like symptoms to full paralysis, and it often hit children the hardest. Some recovered completely, others were left with weakened limbs, and the most severe cases required iron lungs to breathe. During the summer months, when outbreaks were most common, swimming pools were closed and public gatherings canceled.

Rubella

Credit: Getty Images

Rubella was generally mild for most people, often just a low fever and a pinkish rash. But for pregnant women, even a light infection could have devastating consequences. The virus could pass to the fetus and cause miscarriages or birth defects such as blindness, deafness, and heart disorders. In the years before widespread vaccination, rubella epidemics left a heavy toll on maternal health, and many children were born with lifelong disabilities that could have been prevented today with a single shot.

Smallpox

Credit: Getty Images

Smallpox was one of the deadliest diseases in human history. It began with high fever and body aches, followed by painful, pus-filled blisters that covered the body. The virus killed about 30% of those infected, and survivors often carried deep, permanent scars. Quarantine was the only defense before the smallpox vaccine was developed, and even then, access was limited for decades. The eventual eradication of smallpox in the 20th century remains one of public health’s greatest achievements.

Tetanus

Credit: Getty Images

Tetanus came from something as simple as a puncture wound or a dirty cut. The bacteria released toxins that caused intense muscle contractions. Victims developed “lockjaw,” rigid muscles, and painful spasms that sometimes broke bones or stopped breathing altogether. Once symptoms started, there was almost nothing doctors could do.

Cholera

Credit: Canva

Cholera was especially deadly in crowded cities with poor sanitation. It spread through contaminated water and caused sudden, severe diarrhea and dehydration. Without rehydration therapy—which hadn’t yet been developed—patients could die within hours. Outbreaks were common after natural disasters, during war, or in rapidly growing urban areas where sewage systems couldn’t keep up. Cholera moved fast, and public health responses often lagged behind.

Varicella (Chickenpox)

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

As is the case today as well, chickenpox was expected in childhood, but it wasn’t always mild. Most children recovered after days of fever and itching, but some developed bacterial skin infections, pneumonia, or brain inflammation. Adults who caught it often had more serious complications. Before the vaccine, parents often exposed kids on purpose to “get it over with,” but not every case was harmless. For some, it became a life-threatening condition.

Tuberculosis (TB)

Credit: 89Stocker

TB was so common it was sometimes called “consumption.” It spread easily through coughing or even speaking and mainly affected the lungs accompanied with chronic cough, night sweats, fever, and weight loss. Those infected often ended up in sanatoriums, isolated for years with no real cure—just fresh air, rest, and time. TB didn’t discriminate by class or age, and it was responsible for millions of deaths before antibiotics became widely available.

Typhoid Fever

Credit: Getty Images

Typhoid fever spreads rapidly through contaminated water and food, particularly in densely populated cities lacking modern plumbing. High fevers, weakness, and severe intestinal issues kept people bedridden for weeks. Without antibiotics, recovery was uncertain, and outbreaks often swept through families before anyone realized the source of the contamination was unsafe water.

Influenza (The Great Flu)

Credit: Getty Images

Influenza was far deadlier a century ago, especially during the Great Flu pandemic of 1918. With no vaccines or antiviral treatments, even healthy adults fell quickly. Pneumonia followed fast, hospitals overflowed, and entire communities watched loved ones decline within days, sometimes hours, with little doctors could do.