How a Hollywood Bombshell Invented the Tech Behind Wi-Fi

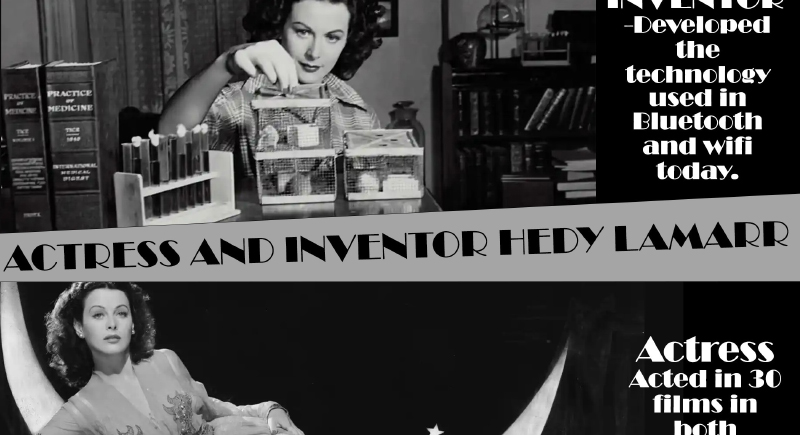

Hedy Lamarr was known to most people as the striking star of films like Algiers, Ziegfeld Girl, and Samson and Delilah – the kind of actor whose presence seemed to fill a theater on its own. Off camera, though, she lived a very different life. After long days on set, she often sat at her drafting table, sketching ideas and working through mechanical puzzles simply because the challenge excited her. The world admired her beauty, but the quiet work she did at home ended up shaping the wireless technology we depend on today.

From Viennese Prodigy To Hollywood Star

Image via Wikimedia Commons/Dr. Macro

Hedy was born Hedwig Kiesler in Vienna in 1914. Her father encouraged her curiosity by explaining how machines worked during long walks, and her mother introduced her to music and theater. By the age of five, she was taking apart her music box just to see how it worked. Her talent for acting brought her to Berlin as a teenager, where she studied with director Max Reinhardt and landed roles in European films.

Her breakout performance in the 1933 film “Ecstasy” brought quick attention, including from Austrian arms dealer Fritz Mandl. They married the same year, but the relationship was suffocating. Hedy was expected to smile on cue, host dinners, and sit quietly while Mandl discussed weapons with powerful guests. She absorbed far more from those evenings than anyone realized. She listened closely to conversations about torpedoes, guidance systems, and radio signals. Those details stayed with her long after she escaped the marriage in 1937 and made her way to London.

Hedy met MGM studio head Louis B. Mayer soon after fleeing Europe. By the time their ship reached New York, she had a contract and a new name inspired by silent film star Barbara La Marr. Hollywood took to her instantly. On screen, she played mysterious, glamorous characters, and off camera, she preferred an evening at her inventing table.

An Inventor Hiding in Plain Sight

Hedy dated Howard Hughes for a time, and he encouraged her ideas. He even gave her equipment so she could work between scenes. She studied the fastest birds and fish and used what she learned to design a sleeker wing for Hughes’s aircraft. He told her she was a genius, and he wasn’t exaggerating.

She came up with plenty of everyday inventions, like a dissolving soda tablet and an improved stoplight, but her most important work grew from her frustration with the war in Europe. By 1940, German U-boats were destroying ships across the Atlantic. Hedy wanted to help the Allies and knew something about torpedo problems thanks to those long, boring dinners during her first marriage.

A chance meeting at a Hollywood party brought her together with composer and inventor George Antheil. They bonded over ideas and grief. Antheil’s brother had just been killed in the early days of World War II. Hedy was heartbroken over the sinking of a British ship carrying evacuee children. They decided to build something that could make a difference.

The Secret Communication System That Changed Everything

Image via Wikimedia Commons/Andrew Eder

Hedy suggested a way to stop enemies from jamming radio-guided torpedoes. If the control signal hopped quickly between different frequencies, no one could block it. Antheil, who worked with synchronized player pianos, helped figure out the mechanics. The two created a system that let a transmitter and receiver switch stations together in perfect sync.

They filed a patent in 1941, and it was approved the next year. The Navy turned it down and told Hedy she could help more by selling war bonds. She did exactly that and raised an incredible amount, including $25 million in one campaign. Meanwhile, the patent sat untouched. Over time, the idea behind their invention became known as spread spectrum. It eventually shaped military tools, early cell networks, Bluetooth, GPS, and Wi-Fi.

A Legacy Finally Recognized

Hedy continued acting through the 1950s, then stepped out of the spotlight. She wasn’t credited for her invention until late in her life. In 1997, she and Antheil received the Electronic Frontier Foundation’s Pioneer Award. She passed away in 2000, but her work lives on in the technology used every day.

Hedy Lamarr didn’t just play brilliant women on screen. She was one. She helped create the backbone of wireless communication, even though few people noticed for decades. Her story is a reminder that talent doesn’t always look the way people expect, and sometimes the biggest ideas come from the most unexpected places.